Resurrection Poem(s)

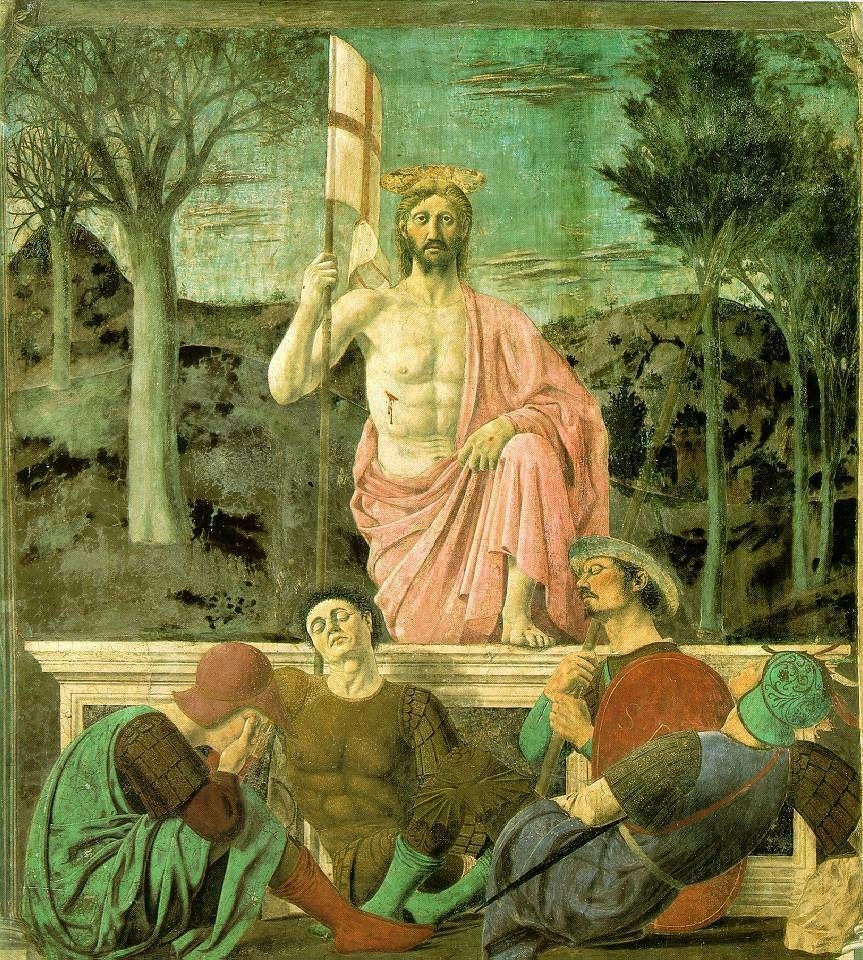

I want to revisit Piero della Francesca’s Resurrection. After sharing a Wendell Berry poem written in response to the painting, I again came across the image in Benjamin Myers’ book, Christ the Stranger: The theology of Rowan Williams. In Christ the Stranger, the fifteenth century work helps introduce the intellectual history of the former archbishop of Canterbury. Myers notes that the “mute eloquence” of visual theology, like frescos and icons, serves as “a leitmotif” in Williams’ poetry.

And so, it turns out, there exists at least two poems in response to this masturful image, by at least two wise and thoughtful contemporary thinkers in Berry and Williams. An embarrassment of riches! What kind of poetry blog would this be if I did not let poetry speak for itself and give the last word. Here now is Rowan Willams poem, “Resurrection: Borgo San Sepolcro.”

Today it is time. Warm enough, finally

to ease the lids apart, the wax lips of a breaking bud

defeated by the steady push, hour after hour,

opening to show wet and dark, a tongue exploring,

an eye shrinking against the dawn. Light

like a fishing line draws its catch straight up,

then slackens for a second. The flat foot drops,

the shoulders sags. Here is the world again, well-known,

the dawn greeted in snoring dreams of a familiar

winter everyone prefers. So the black eyes

fixed half-open, start to search, ravenous,

imperative, they look for pits, for hollows where

their flood can be decanted, look

for rooms ready for commandeering, ready

to be defeated by the push, the green implacable

rising. So he pauses, gathering the strength

in his flat foot, as the perspective buckles under him,

and the dreamers lean dangerously inwards. Contained,

exhausted, hungry, death running off his limbs like

drops

from a shower, gathering himself. We wait,

paralysed as if in dreams, for his spring.